A Living Test Tube: Examining fifty years as an urban university

Posted on: June 1, 2017

This article by archivist Daniel Matthes was originally published in the commemorative 2017 edition of UWinnipeg Magazine.

This article by archivist Daniel Matthes was originally published in the commemorative 2017 edition of UWinnipeg Magazine.

Fifty years ago, a small downtown campus called United College received a charter and became The University of Winnipeg. The charter was granted thanks to recommendations made by the Council of Higher Learning, which recognized that United College could only take advantage of its unique situation in downtown Winnipeg with institutional autonomy.

The 1967 charter began a period of intense self-scrutiny and strategic planning, giving rise to The University of Winnipeg’s identity as an urban university with a social responsibility to the community surrounding it. That urban identity has guided and shaped the University since 1967 — and in turn, downtown Winnipeg itself.

UWinnipeg’s establishment was largely thanks to its first president, Dr. Wilfred Cornell Lockhart. In 1961, as principal of United College, he invited members of Manitoba’s other three church-affiliated colleges (St. John’s, St. Paul’s, and St. Boniface) to collaborate on a report to the provincial government expressing concerns about post-secondary education in the province[1].

The paper led to the formation of the Council on Higher Learning in 1965, and ultimately the granting of charters to Brandon University and The University of Winnipeg in 1967. The meetings of the Council were mostly held at United College, owing to its central location; Dr. Lockhart was a foundational member as well as the Chair of its Arts and Sciences Committee. Independence for United College was not his ultimate purpose, but it was a direct consequence of his planning and thinking.

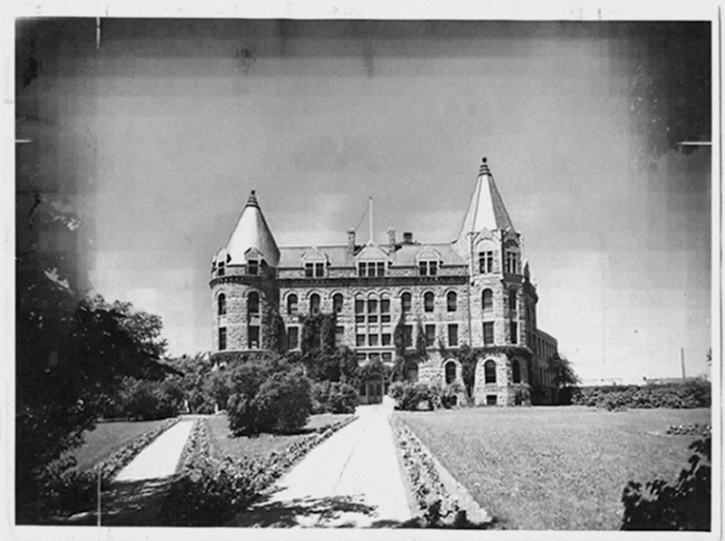

At the time, United College offered a traditionally-structured liberal arts undergraduate program. Its physical campus mirrored the traditional structure of its programming: seven buildings of disparate ages and architectural styles, surrounding a peaceful inner quadrangle that echoed classical campus design, all of it circumscribed by a fence. Beyond that fenced perimeter lay Winnipeg’s 1960s downtown, the problematic subject of urban planning strategies for decades to come. The campus was a sanctuary that provided a sheltered space for conventional scholarly work, but it was intentionally insulated from its urban environment.

The importance of United College’s urban setting was a key factor in the Council on Higher Learning’s recommendations. They did not elaborate on how that role might be realized: rather, as independence approached, the Board of Regents commissioned a study of United College’s administration, curriculum, and facilities by Reid, Crowther & Partners, Ltd. The study culminated in a two-part report: A Recommended General Development Plan for The University of Winnipeg, and described Winnipeg’s core as “a living test tube for United College.”[2] The report made a number of suggestions as to how the new university might involve itself with the development of the area and the education of people working and living therein.

Many of the changes that The University of Winnipeg deployed through the suggestions of the development plan represented an innovative break from a traditional curriculum. For example: the experimental University at Noon program in 1971 was based on a suggestion in the plan for “refresher courses and mid-career educational programs” for professionals working downtown[3]. It was the first such program in Canada,[4] and bore a through-line to the Division of Continuing Education, rolled out in 1974, and to present-day PACE (2012). Other mold-breaking examples with import in the present include the Administrative Studies degree introduced in 1970 and the daycare that began in the basement of Bryce Hall in 1974. These sorts of ventures broke risky ground, but took root and flourished owing to the University’s unique urban situation.

UWinnipeg’s traditional liberal arts curriculum had a reflection in its cloister-like campus; as the curriculum evolved to meet the demands of an urban university, so too did its facilities. One of the first gestures made by President Dr. Henry Duckworth in 1971 was to remove the fence around campus “as an earnest of our good intentions.” He stated as such in his inaugural address just after announcing the aforementioned downtown-wide University at Noon program[5]. The fence’s removal was a small but important symbol of the University being released into the city, as much as welcoming the city into the University.

A responsibility to the surrounding community continued to guide other physical changes to the University’s campus. The most significant was the construction of Centennial Hall, designed to “reach out to the persons living in its vicinity and respond to their needs,”[6] as an embodiment of the University’s then-slogan: “the city is our campus.” The Duckworth Centre and Child Care Worker Training Program, both opened across Spence Street in 1984, are later examples that the University boasted as “tangible, concrete evidence of its commitment and dedication to the community around […] to serve the world beyond its academic population.”[7] They were designed with the needs of the people living in the surrounding neighbourhoods in mind. A similar spirit of community inclusion guided the recent design of the Axworthy RecPlex[8]. These inclusive designs were departures from traditional thinking about the purpose of a liberal arts campus in 1967.

The University of Winnipeg’s impact in its urban role on our downtown cannot be overstated. One need only imagine alternate dystopian futures for Winnipeg, whereby United College had moved to the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry campus in 1958, leaving the downtown to fend for itself; or perhaps where the University had demolished its iconic Wesley Hall and built up a series of office-style high-rises — as several potential expansion plans recommended — instead of Centennial Hall.

Perhaps the University might have been less bold in pushing the borders of its traditional liberal arts curriculum, and never opened the Institute of Urban Studies in 1969. The early work of the Institute, under its director, Lloyd Axworthy, directly informed the 1979 Core Area Agreement.[9] That legislation, of which Axworthy as a Member of Parliament was a signatory, led to the Winnipeg Development Agreement and the North Portage Development Corporation as well as later successors: bodies responsible not only for funding many of the University’s own urban endeavours, but also for shaping downtown as we know it today.

Our downtown without The University of Winnipeg simply would not be the same.

Fifty years ago, a small downtown campus called United College received a charter and became The University of Winnipeg. All the strategic planning of the time pointed to the University’s downtown location as one of its key strengths and rationales for establishment. The idea of the urban university formed a trajectory for UWinnipeg that has carried it to the present, shaping its curriculum and its physical structures to accommodate the needs of the people living and working in its downtown environment. The downtown is not complete — renewal is a living process and takes new shapes alongside society itself. The University’s fifty-year urban legacy, therefore, is only a beginning.

Sources:

[1] United Church Archives PP116, Wilfred C. Lockhart fonds, Council on Higher Learning 1961-1965, File 14. “A submission to the Premier and Government of the Province of Manitoba on behalf of St. John’s College, St. Boniface College, United College, St. Paul’s College,” October 1961.

[2] University of Winnipeg Archives UW-2-1, Development Plans for the University of Winnipeg 1967-1983. “Interim Report of the Examination of Potential Role, Size and Campus Development of United College at Winnipeg, Manitoba,” 26 June 1967, p. 28.

[3] Ibid. p. 29.

[4] University of Winnipeg Archives UW-2-1, File 1. Werier, Val, “Lunch-time classes on Portage.” Winnipeg Tribune, 21 October 1971.

[5] University of Winnipeg Archives AC-18-1, Special Events, File 5, University of Winnipeg – Centennial Celebrations 1971. “The Installation of Henry Edmison Duckworth as President and Vice-Chancellor,” 16 October 1971, p 13.

[6] University of Manitoba Archives, Digital Collections, The Winnipeg Tribune. “New U of W Hall Opened,” 25 September 1972, p. 23. http://libguides.lib.umanitoba.ca/archives, accessed 3 April 2017.

[7] Krotz, Larry: “The Downtown University: Serving Its Community.” University of Winnipeg Journal 2:2 Winter/Spring 1985, p. 5.

[8] Axworthy, Lloyd. “State of the University Address,” 7 September 2012. http://uwinnipeg.ca/president/state-of-the-university-address.html, accessed 2 March 2017.

[9] Krotz, pp. 6-7.

< Back to listing