EALC Fieldnotes: Seoul

EALC Fieldnotes: Seoul by Tiana Mojelsky1

The pandemic became real to me on January 20th, when Seoul announced its first case, an infection that came directly from Wuhan, China. Before then, it was foreign, something we looked at from afar. We would spend time in the breakroom passing our phones back and forth asking, “Are you seeing what’s going on in China right now?” It became a daily routine watching TikToks from Chinese citizens who were locked in their apartments to stop the spread of this thing called Covid-19.

When South Korea confirmed that first case, we were all cautiously optimistic. I was planning my birthday party for the end of February, graduation was coming up quickly, and many of my friends were scheduling their trips home. We all believed Korea had a handle on this--after all, they had been through MERS and SARS2 and had learned the secret to containing scary diseases. Not to mention, there were only a few confirmed cases.

Then, Shincheonji happened.3

On February 20th, suddenly there were 70 new confirmed cases.

104

544

600

800

1,500

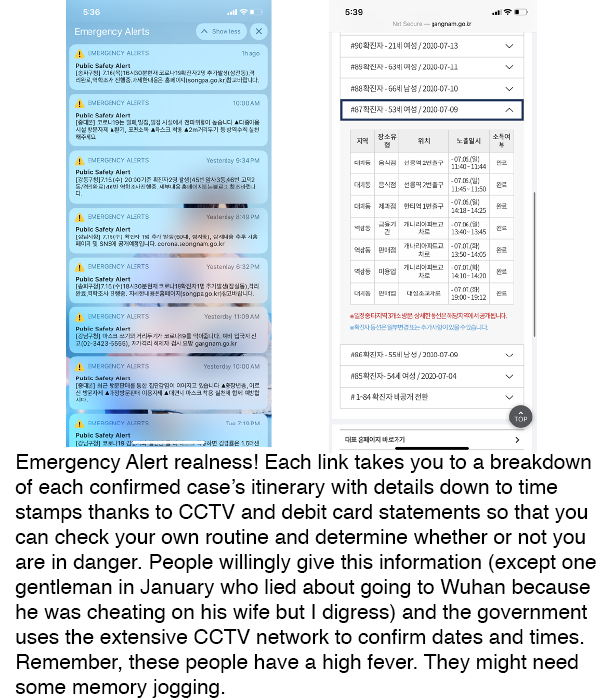

4,200...30 emergency alerts a day...and the first Covid fatality by the time March arrived.

Graduations were cancelled, flights home were moved up, and those of us who stayed were wondering what was going to happen to us. I thought back to those Wuhan TikToks and believed, surely I won’t be locked in my apartment.

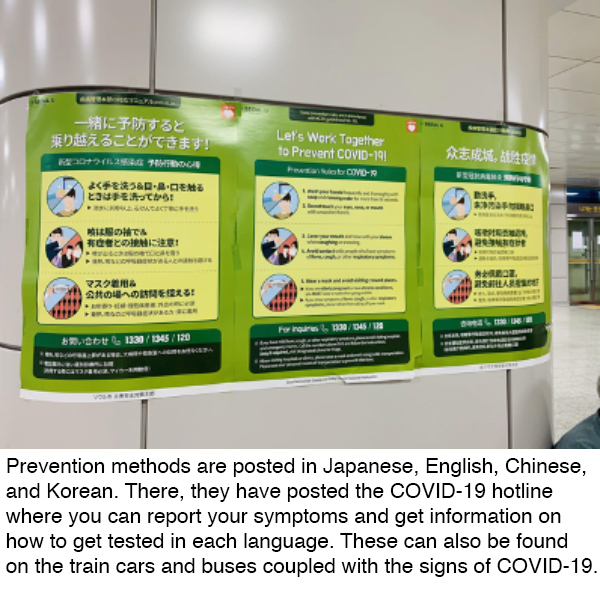

The South Korean government acted fast: public schools and offices were shut down, strict social distancing measures were put into place, and masks were distributed to the public. Still, Covid was mysterious and scary, and we didn’t have the benefit of knowing how the virus worked. The rumour was that it was airborne, so it would be a good idea to wear a mask. The best prevention, according to the government, was to stay home. So that’s what we did.

I was in isolation for the entirety of March 2020. I didn’t go to work, I didn’t celebrate my birthday, I didn’t go shopping, I didn’t get my hair cut (February was a bad month to put that off). Every morning, I rolled out of bed at around 8am and entertained myself in my shoebox apartment while being tormented by the endless stream of emergency alerts.

Each of these was a confirmed COVID case. The government sends an alert whenever they confirm the case and the person is successfully placed in quarantine. Then, they send a followup alert with a link to the government’s website detailing that person’s travel itinerary and whether or not they wore a mask. If you were in close contact with that person, you were legally required to be tested. If you were simply in the same area, you were strongly encouraged to be tested.

Isolation was hard, but I did go to cafes on occasion just to get out of my apartment. In Seoul, businesses never shut down. However, they did reconfigure their seating to accommodate the social distancing measures set out by the government. No one could sit next to each other, and masks were absolutely required except when you brought food or drink to your mouth.

Upon returning to my apartment, I went through a 4-step process:

- Wash my hands for 20 seconds, rinse for 10 seconds (I usually sang the chorus to Raspberry Beret or recited Shangela’s sugar daddy speech to keep time)

- Disinfect all of the items I took with me (phone, wallet, debit card, etc)

- Wash my hands again because I inherited OCD (thanks, dad!)

- Throw out my mask

The first time a case was confirmed in my neighbourhood, I didn’t leave my apartment for four days straight.

Luckily, I live in the same building as most of my coworkers who also happen to be my friends. We were able to see each other as often as we wanted, but even that was stressful. I couldn’t tell who was taking this seriously and who wasn’t. Sure, I was going to cafes still, but were they also following my Super Effective Four Step Program for Cleanliness? Who knows.

So, I tried to stay in as much as possible. My Korean friends were starting the Dalgona Latte4 trend while I bothered my girlfriend, faked being productive, and desperately collected fruit to pay off Tom Nook.

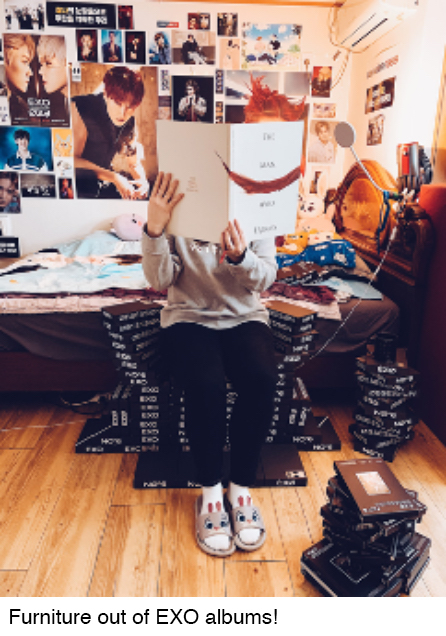

Strangely, even though I had all this time on my hands, I didn’t talk to my friends and family back home too much. Frankly speaking, I was a little bit resentful. Jokes...Memes...videos of young adults proclaiming “It’s Corona Time!” as they drank from Corona bottles (or pretended to). At a time when Canada had yet to experience the outbreak, it was Day 28 of regulated isolation in Seoul, where I was building furniture out of my K-pop albums because I was bored out of my mind.

Eventually as Covid did make its way into Canada and the USA, I tried to give advice to my friends and family. Stay at home, use a mask, wash your hands a lot. I began to worry about my family. Prime Minister Trudeau had summoned Canadians to come back home, and my dad was traveling in the States. I have an elderly grandmother who I love with my whole heart. My family and friends mean everything to me. I had been going through this nightmare for over a month, but I didn’t want them to have to experience this. Covid’s arrival in Canada, though inevitable, was the thing I dreaded from thousands of miles away.

I returned to work on April 6th, six weeks after our school closed down. So much had changed. Cases have gone down, way down, but my life became much more stressful than it used to be. Everyone in our school is required to wear masks and to maintain distancing. My students sit one metre apart with a plastic partition between them. We sanitize and wash our hands multiple times a day. Masks only come off for meals. We try to keep as much control as possible inside the classroom.

Still, Covid looms over our lives, creating overwhelming stress in the workplace and at home. We all share the same fear: what if I am the one that catches it? What if it is I who brings it to school? Over and over, we are told not to go out because if we have to close the school, everyone loses. That stress is untenable. I don’t want that responsibility, but I put myself at risk by even leaving for work every day.

Then we were treated to a serving of xenophobia and homophobia. On May 5th, a person exhibiting viral symptoms visited a nightclub in Itaewon. This case generated a small outbreak, which also infected a foreign teacher for the first time. To make things worse, this new Patient Zero also had visited a gay club. Conservative newspapers published articles condemning both foreigners and homosexuals, consequently targeting these minority groups as the cause for the new rash of cases. As someone who belongs to both of the groups, I unfortunately was compelled to cancel most of my plans again. I was scared again.

The only outing I made at that time was a visit to a special exhibition, one that I had been looking forward to since last November. At that exhibition, I had to write down my full name and phone number. I also had to wear a mask and gloves for the entirety of the stay. But the weight of guilt I felt after that event was oppressive.

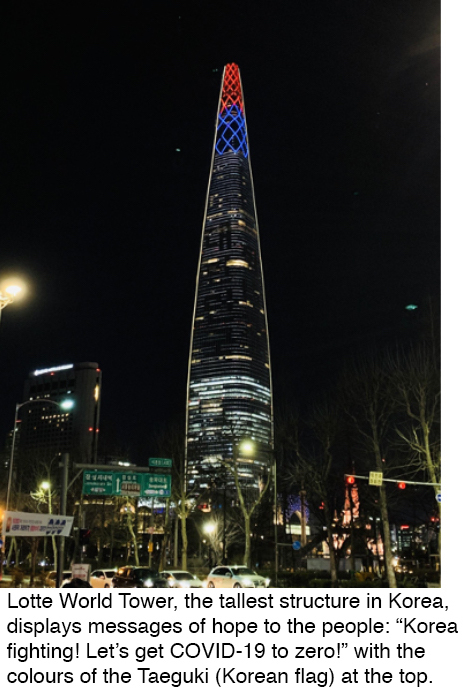

Now, as the virus has abated somewhat, I don’t spend all my weekends indoors. I see my friends, and we wear masks. I wash my hands. I order groceries instead of going to the store. I follow the rules because following the rules is what saved us the first time around. So much has been written about why South Korea is a Covid success story, many with far more eloquence than I can muster. Seeing how an outbreak could emerge even after containment, I believe all basic advice bears repeating.

Wear a mask. I wear a mask at work for over 8 hours a day, and I continue to wear it if I go anywhere other than home after that.

Is it uncomfortable? Yes. I’ve had to visit the dermatologist twice because my lips had become inflamed from contact dermatitis.

Is it hot? Yes. Extremely. The summer monsoon season isn’t working any wonders either.

But Korea is a success story because we do wear masks. It is the law to wear masks on public transit and in public enclosed spaces. It’s not an age thing either. I also see most people walking down the street or sitting in a park wearing their mask. Even my six year old students wear their masks all day without a single complaint. At this point, with all of the information we have, it is incredibly selfish not to practice this one, simple step.

I’ve come to the realization that there isn’t going to be a quick fix. I’m in Month Six of living in the time of Covid. Even with all of these preventative measures in place and support from the government, the stress is nearly unbearable. Every little cough, every tickle in the throat, any slight increase in temperature sends a bolt of fear through my heart. The only thing that I can do is continue to follow the rules and hope for the best.

Studying about and living in East Asia has afforded me much experience and insight into different perspectives on global issues. One key difference between the West and East Asia that I find myself thinking about is the focus on the individual vs the collective. This contrast is even more evident with the Covid pandemic. For many in Western countries, wearing a mask is not a protection of the self and thus does not seem to be as valued. Here in Korea, protecting only the self has no benefit. Particularly in the States, the pandemic numbers are simply astounding due to a deadly combination of ignoring the severity of Covid and failing to consider the health of the collective. Korea traditionally places importance on the whole of the community and doing what is best for everyone--wearing that mask. That is the only “secret” to Korea’s success with Covid-19.

Should we become able, if only for a moment in time, to value the collective over just the self, we might be able to stand a better chance of fighting this pandemic.

Footnotes:

1 Tiana Mojelsky is a 2014 graduate of the University of Winnipeg's East Asian Languages & Cultures Program. She has since experienced living abroad in both Tokyo, Japan and Seoul, South Korea.

2 MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) had an outbreak in Korea in 2015. SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome) had a minor outbreak a few years earlier.

3 Known as the Church of Jesus, it led to an outbreak as a cluster of cases among the practitioners spread outside the community.

4 A blended, whipped coffee.